The Festival of Britain (1951) beyond London

Abstract

This article takes a focussed look at how the Festival of Britain was marked outside the main events in London, with an examination of what was organised in Wales and in particular in the city of Swansea. It asks how national was the Festival of Britain, which was intended to convey a sense of national identity.

Context and purpose

1After the end of the Second World War in Europe, the general election held in the United Kingdom on 5 July 1945 returned a Labour government with a landslide victory and a majority of 145 seats in the House of Commons. The Labour government, led by Clement Attlee, implemented a programme of sweeping social and economic change. In 1947, in a context of continuing rationing, deprivation, shortages, when 2 million people were unemployed and there was a shortage of foreign currency to buy food overseas, the Deputy Prime Minister, Herbert Morrison, proposed a festival to mark the centennial of the Great Exhibition of 1851.

2However, the new festival was intended to celebrate Britain as a nation and its achievements. A prime idea was that the festival should help to boost morale and be “a tonic to the nation”. Unlike its 19th century predecessor, it was decided not to refer to the Empire, but the wish was to focus instead on the viability of British democracy and to show the vibrant cultural life in Britain. The idea of holding up a mirror to the nation was to show British people “winning the peace”, when the international background of the early years of the Cold War was one which contained the looming threat of nuclear war.

3Projecting and celebrating a sense of national identity was closely linked to Memory, remembering who the British were, which chimed with a national sense of place, as the rebuilding of Britain led to rethinking a national sense of place. The Land and the People was therefore the theme: a national display of the interwoven serial story of Britain. The architects and designers involved were strongly influenced by their attachment to the land of Britain and the history of the place. Yet, while being in tune with the past, there was a strong emphasis on design, art and architecture. This was allied with attempts to market the project – and the country – and attract victors from UK and overseas, although in the end the only tourists who visited Britain were mainly expats.

4There were objections to the Festival and these included the extensions made to licensing hours, meaning the pubs could stay open longer. The Festival was viewed by some as a ludicrous imposition at a time of hardship and left-wing critics viewed it as a waste of time and a diversion of funds at a time when Britain was in dire need of new housing and job creation. Right-wing objectors viewed the whole thing as socialist propaganda seeking to publicize the new Britain envisaged by the Labour government.

5Nevertheless, committees and bodies were set up, for example the Council on Science and Technology and one on Town Planning and Building Research. Existing organisations were mobilised: the Council of Industrial Design, the Arts Council, the Central Office of Information and the British Film Institute. The Church of England and the National Book League became involved. There was optimism that people would spontaneously join in and respond, and that the Festival would inspire unofficial manifestations but on the whole there was little public exuberance.

6The Festival of Britain centred on London and although ideas were mooted for the organisation of tours of the exhibition around the country this suggestion was quickly abandoned as it would have been too expensive to carry out. Nevertheless, events were organised all over the United Kingdom and not just in London. In many cases these events would have taken place anyway, but in the summer of 1951 they were labelled as part of “Festival of Britain”. As the souvenir guide to the South Bank Exhibition in London explained:

- 1 Ian Cox, The South Bank Exhibition, A Guide to the Story It Tells, London 1951, H.M. Stationery Off (…)

The Festival is nation-wide. All through the summer, and all through the land, its spirit will be finding expression in a variety of British sights [sic] and a great range of British sounds. Taken together, these will add up to one united act of national reassessment, and one corporate reaffirmation of faith in the nation’s future.1

- 2 BBC, On this day. 28th May, «1951 : Glasgow powers up for the Festival ».

7Focus was given to each of the ‘four nations’ of England, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales although the Festival sought to portray Britain as a cohesive singular nation, with diverse cultures, but existing as a seamless whole, one of whose symbols was a common language. This message was repeated at the opening ceremony of the Glasgow Festival of Britain Exhibition of Power. “It is a well-deserved compliment to the land of so many famous engineers and inventors,” said Princess Elizabeth, adding that “the exhibition – like all of the Festival of Britain – belongs to the whole country”.2

A national festival?

8However, was it really “national”? Was all of the United Kingdom really encompassed in the Festival or did London dominate? Half of the official exhibitions were held in London (South Bank Exhibition site, Exhibition of Science, Exhibition of Architecture and the Battersea Pleasure Gardens) with one in Scotland (Exhibition of Industrial Power in Glasgow) and one in Northern Ireland (Ulster farm and factory exhibition in Belfast) while there were none in Wales. There was a travelling exhibition by land and a Festival ship, the Campania, that berthed at Plymouth. But the aim was to present a cohesive, single ‘story’ about Britain and so there was not really any place for representing the multiple national traditions and differences within the nation-state. Nevertheless, outside London, many events were in fact organised but there is no list or record of these, compiled in one central comprehensive way. No websites or authoritative books (such as The Festival of Britain Harriet Atkinson, 2012) indicate the existence of any such archive.

- 3 R. C. Richardson, « Cultural Mapping in 1951: The Festival of Britain Regional Guidebooks » Literat (…)

9A series of 13 guides to regional areas was however produced, based on pre-war guides which had been sold to newly affluent middle-class tourists, but those produced in 1951 were different in that they depicted “ordinary” Britain alongside the usual picturesque attractions. The idea was to update people’s ideas about how Britain looked and so they simultaneously depicted industrial structures and rural traditions. Like the Festival itself they had something of a pedagogical side as they explained Britain’s topography and the way people lived, showing the history and diversity of the British Isles, yet depicting a modern technologically advanced nation. Each guide was quite highbrow and expected readers to be educated and with an ability to draw on literary and historical knowledge, which begs the question of the Festival of Britain and class as well as associated factors such as level of education and disposable income.3

- 4 Joseph McBrinn, « Festival of Britain in Northern Ireland, 1951 », Perspective, pp.16-17, 26-27, n. (…)

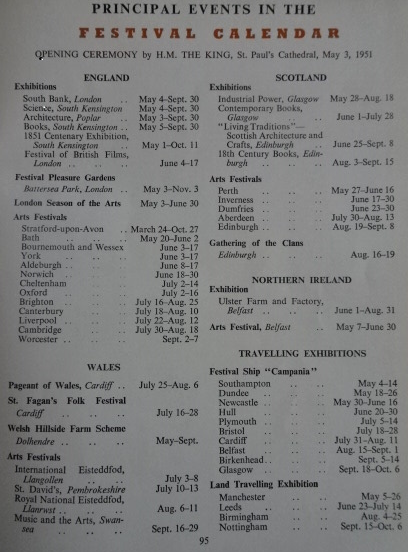

10Events were held in many major English cities: Birkenhead, Glasgow, Manchester, Leeds, Birmingham and Nottingham, and in Scotland events were focussed on Glasgow and Edinburgh. Exhibitions included one on Industrial Power and another on Contemporary Books in Glasgow, a centre of heavy industry, while Edinburgh held a “Living Traditions” event on Scottish Architecture and Crafts and an exhibition on 18th century Books. Arts Festivals were incorporated into the Festival as well as the annual Gathering of the Clans. In Northern Ireland the major event was the Ulster Farm and Factory Exhibition in Belfast, where industry and countryside were celebrated and two farms were built: an 1851 farmhouse and a Farm of the Future.4 As elsewhere, Arts Festivals, which would have been held anyway, were given a Festival of Britain label.

Figure 1. Principal Events in the Festival Calendar. Source : South Bank Exhibition London 1951, Festival of Britain Guide, HMSO, 1951, p.95

Focus on Wales

11In the absence of any large-scale definitive study of this period, when trying to establish an idea of what the Festival of Britain entailed outside London, research on the internet and then in local libraries revealed that the summer of 1951 was celebrated in quite an extensive way in Wales, and this probably holds true for the rest of the UK.

- 5 A Pathé film clip shows some aspects of this event but fails to include any reference to the Festiv (…)

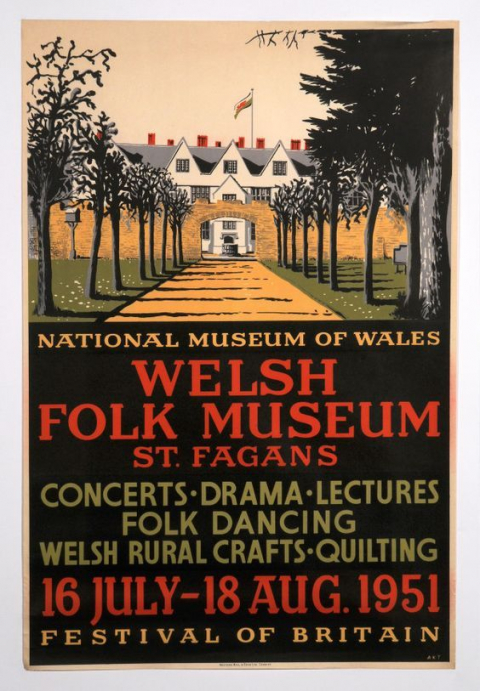

12The Festival Office in London and the Welsh Festival Committee had decided that for Wales the annual celebrations of Welsh culture in Llangollen – the eisteddfodau – would be Wales’ contributions to the Festival.5 A few other events have been recorded in central archives, and these included a Pageant of Wales (25 July-6 August) and St Fagan’s Folk Festival (16-28 July), both held in Cardiff. This all added up to a distinctly quaint & rural representation of Wales which is perhaps not surprising. In 1951, unlike Scotland, Wales did not have a capital city (Cardiff was named as such in 1958) nor did it enjoy representation at national level, as the Welsh Office and a secretary of state for Wales in the cabinet did not exist until 1964.

Figure 2. Welsh Folk Museum, Festival of Britain poster. Source : Fflur Morse ‘A Tonic to the Nation’: St Fagans and the Festival of Britain 1951, National Museum of Wales

- 6 Harriet Atkinson, The Festival of Britain: A Land and Its People, I.B.Tauris, 2012, p.119.

13Continuing the rural theme, the most ambitious plan seems to have been the Welsh Hillside Farm Scheme, at Dolhendre. This was an improved farm building scheme, where the ultimate aim was to show that the government was competent in farm management, a not unimportant fact in a post-war context of land being surrendered to central authority as a means of paying greatly increased death duties. This farm scheme is described as “the only significant Festival event in Wales” by a leading publication on the Festival of Britain6 but this ignores what seems to be quite considerable but hidden or forgotten evidence in local archives (newspaper cuttings, photos..) that many gatherings, large and small, including neighbourly street parties and concerts, were held in Cardiff (the Festival ship, Campania docked in Cardiff for twelve days from 31st July) and across Wales.

14Focus here will turn in particular to Wales’ second city Swansea. The public library holds a collection of miscellaneous documents gathered in one volume Festival of Britain Swansea Events 1951. The person who gathered together these items may have been a Mr L. Rees as his name is on several invitations from the Mayor of Swansea, to the official opening on 2 June, to a film and to an exhibition of Swansea pottery.

15The Festival programme in this collection announces a very extensive variety of activities organised throughout the city and its suburbs for the four months duration. It is interesting to note that the Festival opens with specially dedicated services in the different churches in Swansea (Church of Wales (Anglican), Roman Catholic and Methodist) while the History of the Prayer Book was the subject of a pageant in the first week and early in July Sunday School pupils put on a similar show. There was also an exhibition on work done by Welsh missionaries.

- 7 History of the Swansea Festival of Music and the Arts, West Glamorgan Archive Service, Reference GB (…)

16Not unusually for Wales there are many concerts and musical events: brass bands, chamber music, male voice choirs and the Royal School of Church Music Welsh Regional Festival was held in the Brangwyn Hall which was also the venue for a series of concerts given by the London Philharmonic Orchestra. In September, the fourth annual Swansea Festival of Music and the Arts closed the Festival of Britain celebrations in the town with seven concerts, one of which premiered an oratorio by Welsh composer Arwel Hughes.7

- 8 See for example the amateur film, Pentrebach: Festival of Britain Cricket Match, showing the Royal (…)

- 9 Non League Football Information: History: Festival of Britain football matches, 7th – 19th May 1951

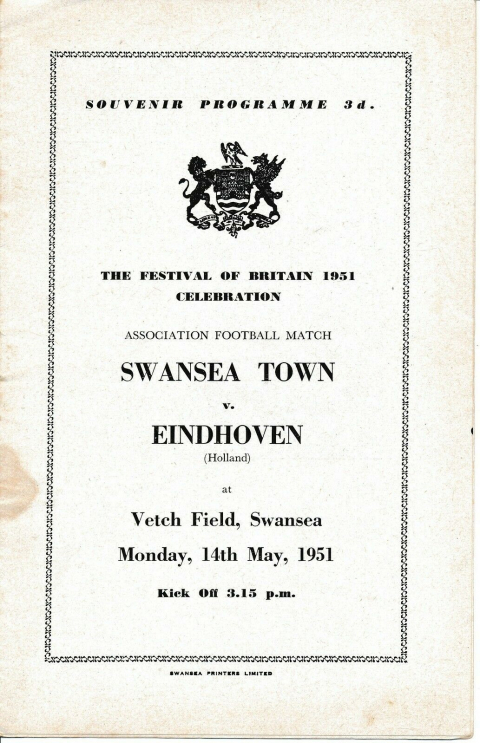

17Drama, theatre, plays and dramatic representations or pageants were numerous. Many exhibitions were organised: photography, needlework, art, porcelain, and pottery, as well as one on industry and another on horticulture. Hobbies were showcased in different events and venues: chess, philately, arts and crafts and model engines and aircraft. Sporting encounters for children and adults included bowls, football, rugby, cricket,8 a youth olympiad and a sailing regatta. A demonstration of lawn tennis by Fred Perry and Dan Maskell on 12 July must surely have drawn the crowds just as rugby matches against specially invited teams (South Africa and an international team drawn from England, Ireland, Scotland and France) and a Swansea-Eindhoven friendly football match on 14 May, organised by the Football Association as part of a series of nationwide end of season Festival of Britain games,9 would have done.

Figure 3. Souvenir programme, The Festival of Britain 1951 Celebration. Association Football Match. Swansea Town v. Eindhoven. 14th May 1951. Source : private collection

18Women ‘s groups and youth associations (Scouts, Guides and Boys Brigade) are present on the programme with different kinds of activities. The armed services took a full part in the local festivities: HMS Sheffield visited the city between 12 – 17 July and there was an RAF pageant.

19More intellectual offerings were made by the university which organised several exhibitions and talks as well as an Open Week. A printed document from the University of Swansea describes the institution and the events of Festival week. The city library had displays and exhibitions too on Literary Swansea, which concerned local authors, including Dylan Thomas, as well as books about the city. A major sector of the Welsh economy was on display at a large agricultural show and in September a week was devoted to Trade and Shopping. The collection of documents in Swansea Library also include type-written histories of Swansea and brief biographies of local authors as well as information and bibliographies on the history of music in Wales.

20As a whole, as portrayed in this Swansea archive and from the official events organised throughout Wales, the Festival of Britain in the principality seems to have projected a picture of idyllic country activities, of artistic and sporting prowess, and ignored the industrial input of Wales, the coal mines (although a mural by Josef Herman portraying Welsh miners was displayed in the Minerals of the Island section of the South Bank Exhibition)10 and steelworks, the docks and railways. These were given prominence during the Festival, but had been concentrated in the Exhibition organised in Scotland, notably the Festival of Britain Exhibition of Industrial Power, held at Kelvin Hall, Glasgow.

Conclusion

21The Festival of Britain has been forgotten these days. This could be due in part to the immediate dismantling of Festival infrastructure by the Conservative government elected in October 1951. The only permanent edifice has been the Festival Hall on the South Bank of the Thames. If it had been a high point in post-war national life it was quickly replaced in public memory by the accession of Elizabeth II and the excitement and preparations for the Coronation in June 1953. It seems to have been just a particular moment in the nation’s hi/story.

- 11 William Hepburn, « Glasgow’s Forgotten Exhibition: The Festival of Britain at Kelvin Hall, 1951 », (…)

22The fact that the Festival was vast and amorphous and not really centrally controlled or managed despite official focus on London may well have contributed to its being forgotten. In both Wales and Scotland, little remains of what was a transient cultural event. The Industrial Exhibition in Glasgow seems to have been forgotten too, despite its celebration of the industrial and cultural heritage of Scotland.11 Perhaps the fact that television was not well developed and there was no widespread media coverage also led to the Festival just fading away. Obtaining a more complete picture of how the nation celebrated itself in the summer of 1951 would require many hours of diligent research in local libraries in the hope that some documentation might turn up.

Notes

1 Ian Cox, The South Bank Exhibition, A Guide to the Story It Tells, London 1951, H.M. Stationery Office, 1951, p.6.

2 BBC, On this day. 28th May, «1951 : Glasgow powers up for the Festival ».

3 R. C. Richardson, « Cultural Mapping in 1951: The Festival of Britain Regional Guidebooks » Literature and History, November 2015, Vol. 24: 2, pp. 53-72.

4 Joseph McBrinn, « Festival of Britain in Northern Ireland, 1951 », Perspective, pp.16-17, 26-27, n.d.

5 A Pathé film clip shows some aspects of this event but fails to include any reference to the Festival of Britain. «International Music Festival. National Eisteddfod Festival. Llangollen, Wales» British Pathé, 9th July 1951, Film ID:1461.34.

6 Harriet Atkinson, The Festival of Britain: A Land and Its People, I.B.Tauris, 2012, p.119.

7 History of the Swansea Festival of Music and the Arts, West Glamorgan Archive Service, Reference GB 216 D 59/3/2, Dates of Creation 1950-1957.

8 See for example the amateur film, Pentrebach: Festival of Britain Cricket Match, showing the Royal Welsh Show held in 1951.

9 Non League Football Information: History: Festival of Britain football matches, 7th – 19th May 1951.

10 Josef Herman, Miners (1951), Glynn Vivian Art Gallery, Swansea.

11 William Hepburn, « Glasgow’s Forgotten Exhibition: The Festival of Britain at Kelvin Hall, 1951 », April 6, 2016.

List of illustrations

|

|

|---|---|

| Caption | Figure 1. Principal Events in the Festival Calendar. Source : South Bank Exhibition London 1951, Festival of Britain Guide, HMSO, 1951, p.95 |

| URL | http://journals.openedition.org/mimmoc/docannexe/image/3625/img-1.png |

| File | image/png, 247k |

|

|

| Caption | Figure 2. Welsh Folk Museum, Festival of Britain poster. Source : Fflur Morse ‘A Tonic to the Nation’: St Fagans and the Festival of Britain 1951, National Museum of Wales |

| URL | http://journals.openedition.org/mimmoc/docannexe/image/3625/img-2.jpg |

| File | image/jpeg, 96k |

|

|

| Caption | Figure 3. Souvenir programme, The Festival of Britain 1951 Celebration. Association Football Match. Swansea Town v. Eindhoven. 14th May 1951. Source : private collection |

| URL | http://journals.openedition.org/mimmoc/docannexe/image/3625/img-3.jpg |

| File | image/jpeg, 436k |

References

Electronic reference

Moya JONES, « The Festival of Britain (1951) beyond London », Mémoire(s), identité(s), marginalité(s) dans le monde occidental contemporain [Online], 20 | 2019, Online since 21 May 2019, connection on 12 November 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/mimmoc/3625 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/mimmoc.3625

Copyright

Mémoire(s), identité(s), marginalité(s) dans le monde occidental contemporain – Cahiers du MIMMOC est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International.