Farewell to Hong Kong. Image from Stand News, used with permission.

The following story was originally published in Chinese on Stand News. It was translated into English by Global Voices and will be published here, with permission, in five different parts. Part One of the series follows.

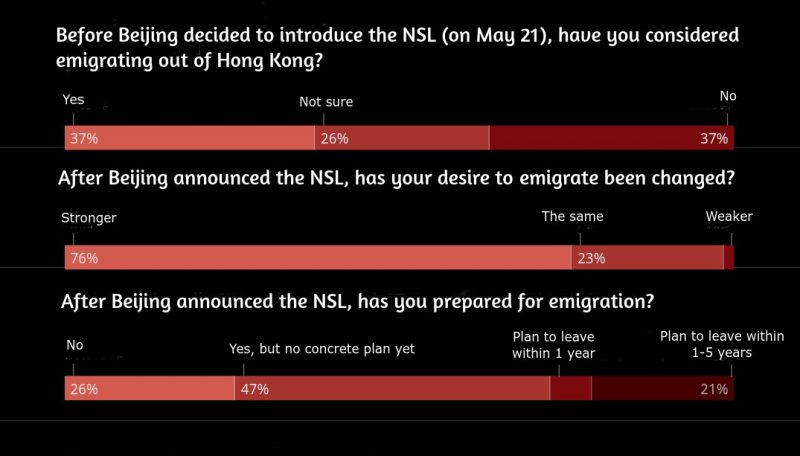

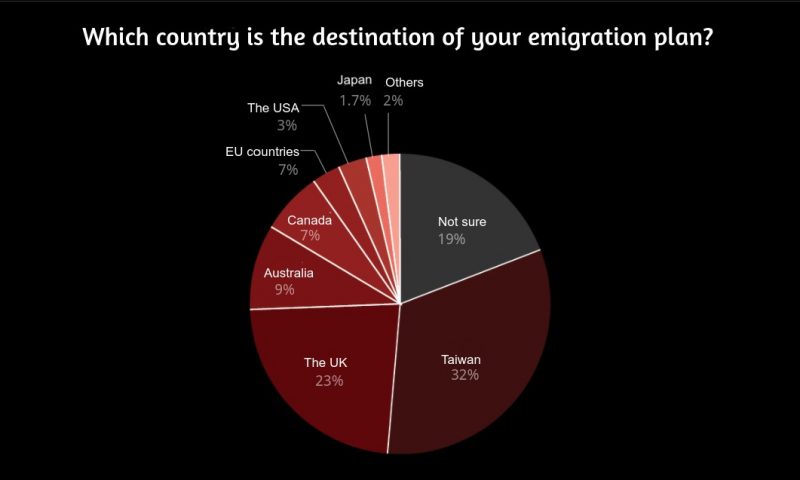

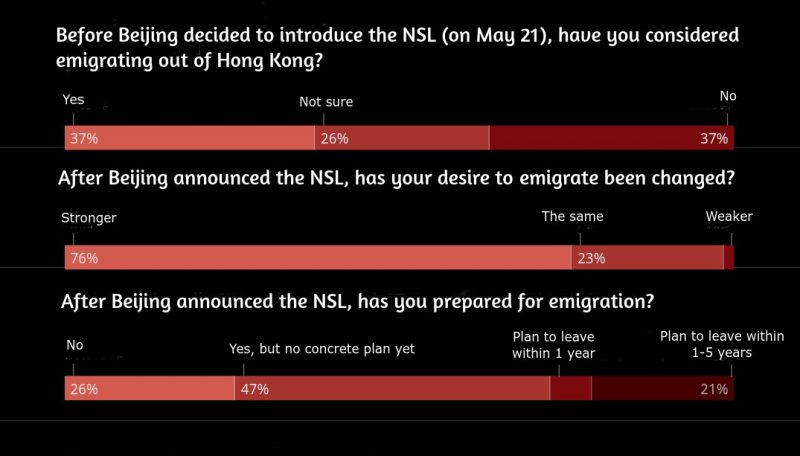

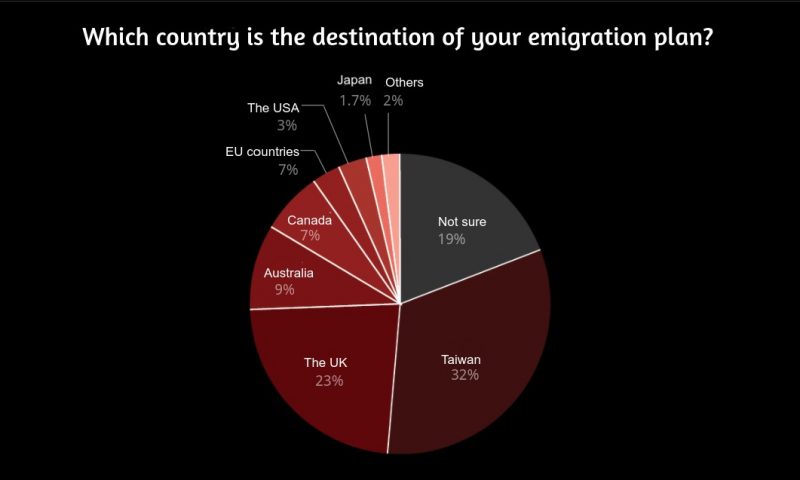

Between August 29 and September 1, Stand News asked its readers in Hong Kong, through a series of online polls, how the national security law has impacted their lives.

More than 2,580 people responded — and about 37 percent revealed that even before the Steering Committee of the National People Congress announced its decision to implement the national security law on May 21, they had considered leaving Hong Kong. Since the law’s enactment, 76 percent of respondents said their desire to emigrate had intensified.

The most popular destination for relocation is Taiwan (32.3 percent), followed by the United Kingdom (23 percent).

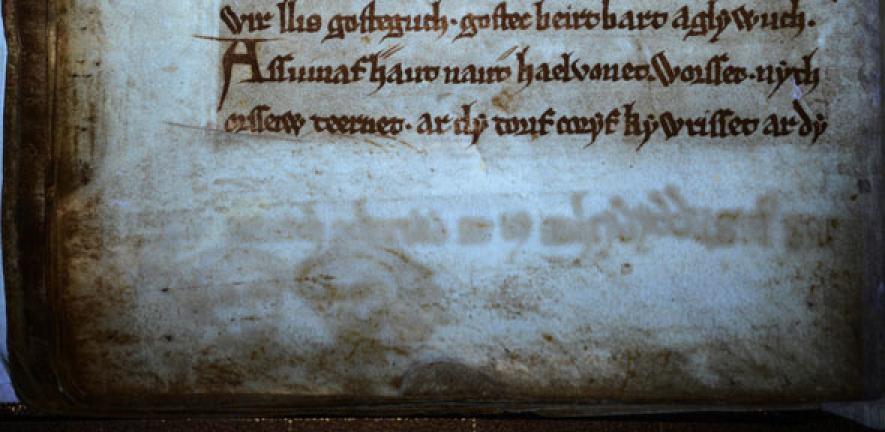

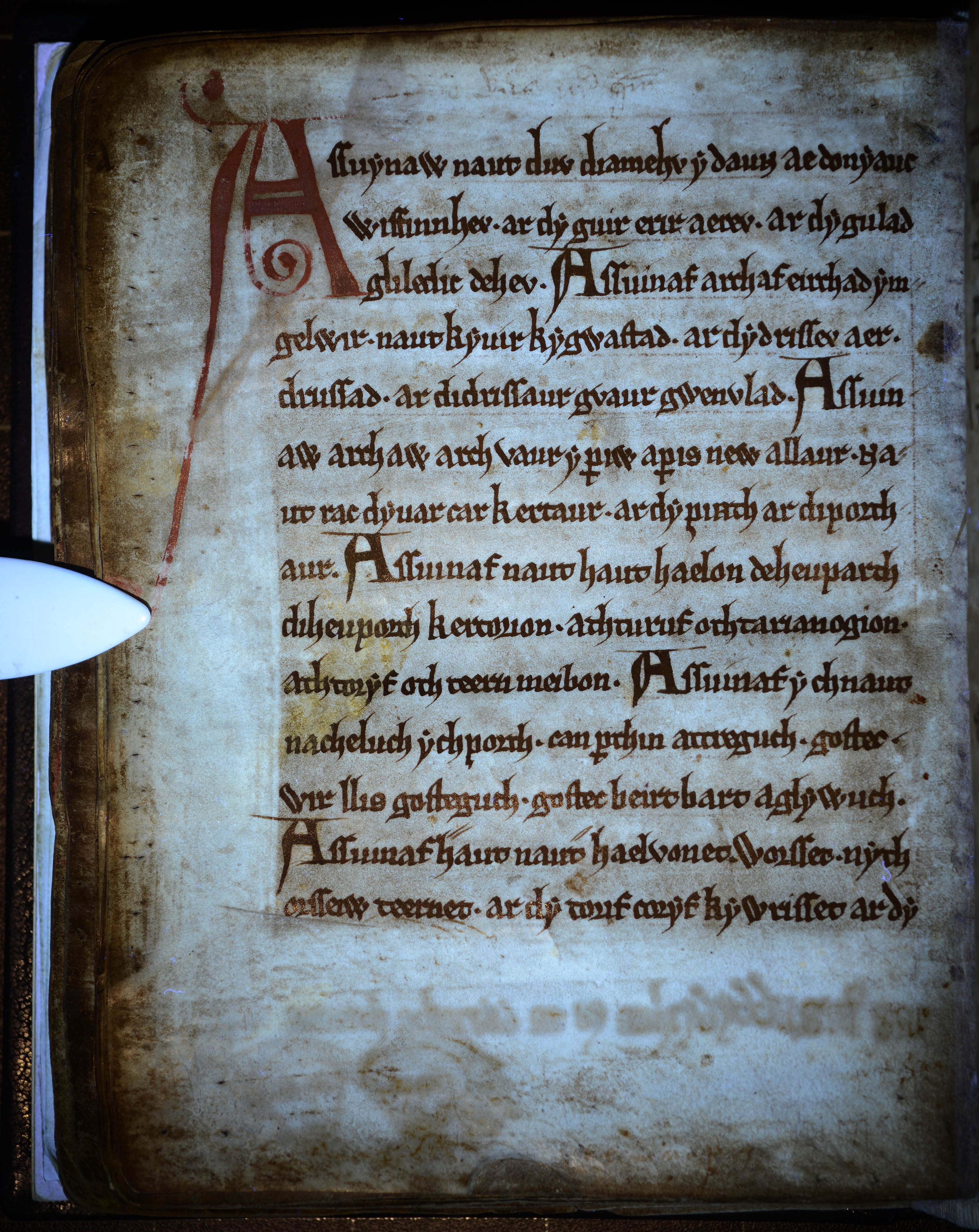

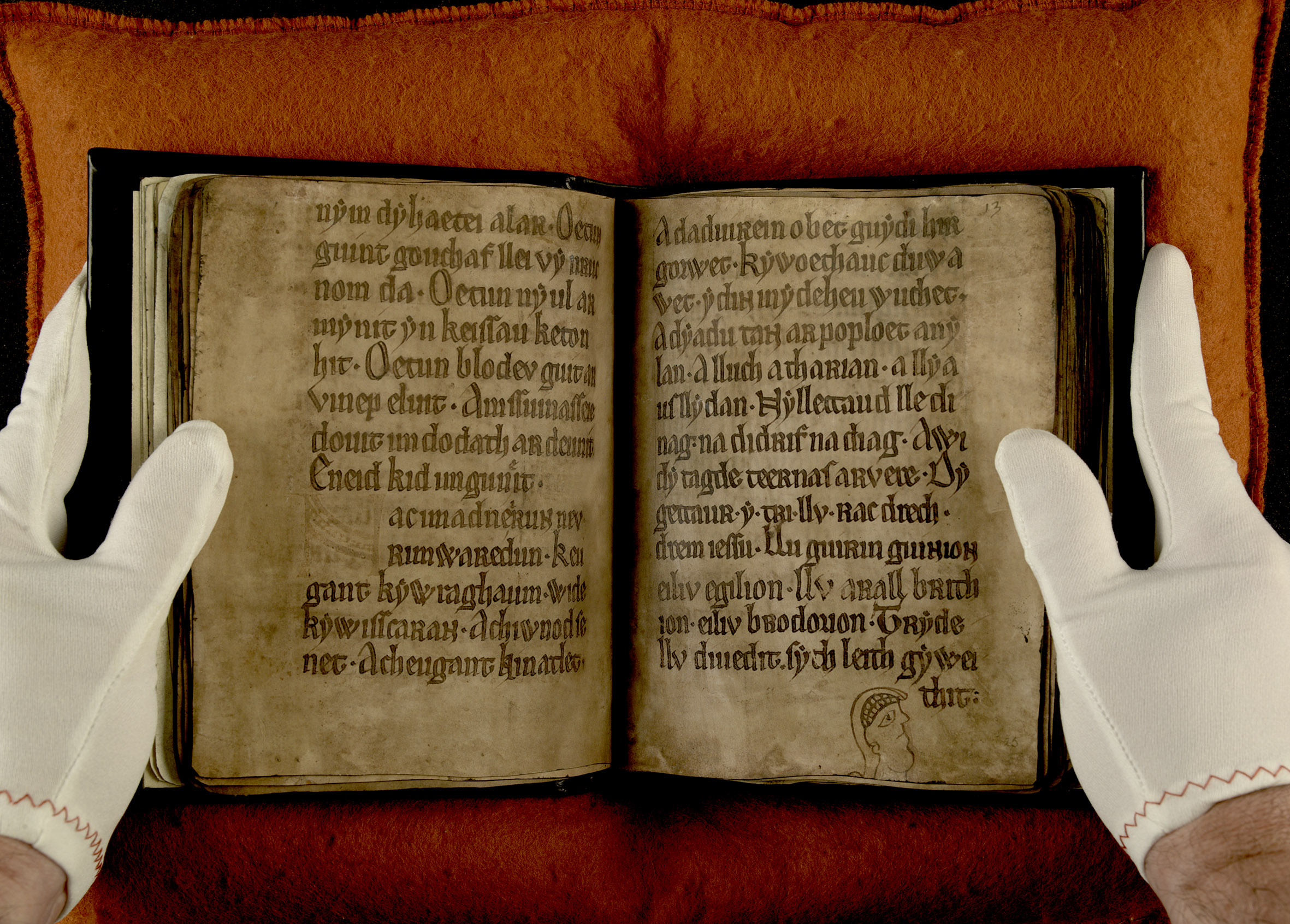

Stand News’ reader survey on emigration attitude.

On July 22, the UK government introduced a policy that facilitates the emigration of residents from its former colony, by allowing eligible Hong Kong British National (Overseas) passport holders and their family members to settle in the UK for work and study. After five years of residency under this British National Overseas (BNO) arrangement, they can apply for full citizenship.

The new immigration scheme will begin accepting applications in January 2021. For now, though, eligible Hongkongers can apply to enter the UK based on “Leave Outside the Rules” (LOTR) — guidelines that allow UK Immigration to exercise discretion on the basis of compelling compassionate grounds.

YM [pseudonym] and her family decided to use this option. They left Hong Kong and, upon their arrival in the UK on August 6, applied for “Leave Outside the Rules” entry. Along with about ten other Hongkongers who were queuing up for the interview, they were asked about their occupation, financial conditions, and religion, as well as about their relatives and acquaintances in the UK.

Born in the 1980s, YM was working as a manager in a public relations firm in Hong Kong, but decided to leave the city with her family in August 2019 after the infamous attack at Prince Edward subway station, in which riot police indiscriminately assaulted passengers in an attempt to arrest protesters.

They sold their apartment for six million Hong Kong dollars (approximately 781,000 US dollars) and lived in a hotel for six months. At first, they planned to immigrate to Cyprus by investing 200,000 Euros in the country, but that plan was put on hold due to the outbreak of COVID-19. When the UK introduced the new BNO scheme, they decided to settle there.

Like tens of thousands other Hongkongers, YM was active during the year-long, anti-China extradition protests. She had joined a number of Telegram groups and made donations to fellow protesters who needed to equip themselves with protection gear. Three of the Telegram groups she belonged to were deleted after their administrators were arrested.

In a protest photo that was widely circulated online, YM’s face was recognisable; quite apart from her worry about getting caught in the cross hairs of the authorities, she told Stand News she was also concerned about her seven-year-old daughter’s education:

The patriotic education would turn her into ‘little pink’. What you learn in the textbooks would no longer be the truth. How could a government treat its young generation like this? In Hong Kong, it is a crime to be young. My daughter is now seven, after a few years, she will be in high school, what would become of her? I don’t want to see her getting arrested.

“Little pink” is a term used to describe young Chinese nationalists on the internet.

Now that YM and her family have successfully entered the UK under “Leave Outside the Rules”, they have started a Facebook page aimed at providing other Hongkongers with information on immigrating to the UK. Within one week, the page received more than 60 inquiries.

YM and her family have since decided to buy a property in the UK, and have no plans to visit Hong Kong in the near future.

Stand News’ reader survey on emigration.

Peter [pseudonym], a civil servant who plans to move to Taiwan with his wife, has signed up for a migration scheme under which he would invest a minimum of HK $530,000 in a Taiwan-based start-up. After five years, he will be able apply for permanent residency.

He chose Taiwan because he believes the fate of Taiwan and Hong Kong are intertwined: “Both Chinese regions are subjected to the tyranny of ‘One China’,” he said:

Taiwan is near to Hong Kong; I can travel back to Hong Kong as frequently as possible. I can also join solidarity rallies in Taiwan and give support to the exile protesters there. In Hong Kong, the space for voicing out has shrunk.

According to Taiwan’s immigration authorities, the island granted 3,161 residency permits to Hongkongers in the first half of 2020. The figure reflects a 116 percent increase when compared to 2019.

Many of those who don’t plan to emigrate — or want to but still haven’t left — have transferred their savings to offshore bank accounts, since the national security law gives police the power to freeze the assets of anyone being investigated. In the Stand News reader survey, 55.8 percent of respondents admitted that they’ve considered transferring their savings abroad, with around 27.8 percent having already moved their money into foreign accounts.

Mr. Lam [pseudonym], an environmental project engineer, made the decision to transfer his savings to an offshore account in May, soon after Beijing announced the implementation of the national security law. He feared that, like mainland China, Hong Kong would restrict foreign currency exchanges, or that the Hong Kong/US dollar peg would be undermined as a result of US sanctions. He therefore converted his HK $10 million nest egg into US currency and moved the money to bank accounts in Singapore.

Since Mr. Lam is already in his fifties, he is considering emigrating from Hong Kong upon his retirement. As a BNO passport holder, one of his options is to settle down in the UK, but he has also considered applying for a retirement visa to Thailand, as the country only requires a savings account worth HK $200,000 in order to apply for residency.

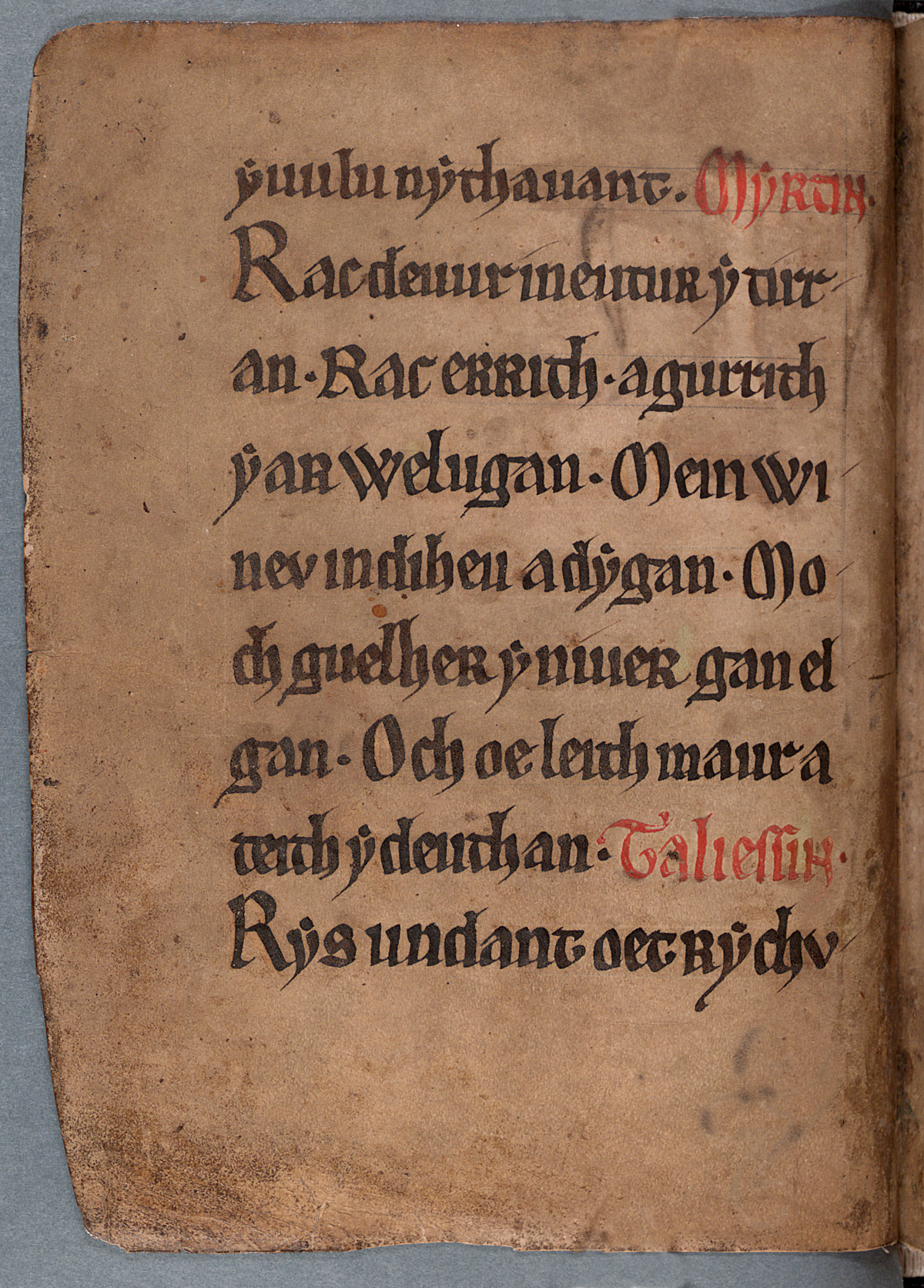

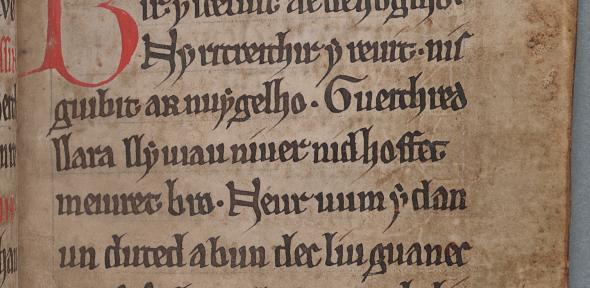

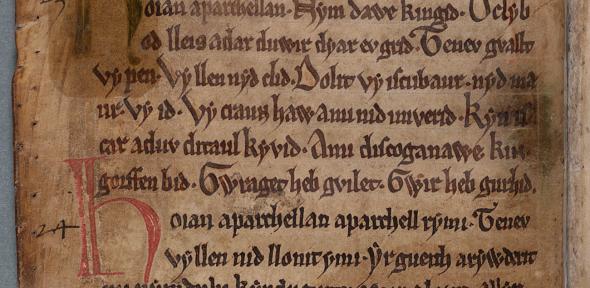

Swansea Castle was founded by Henry de Beaumont in 1106 as the caput of the lordship of Gower, in Swansea, Wales.

Swansea Castle was founded by Henry de Beaumont in 1106 as the caput of the lordship of Gower, in Swansea, Wales.