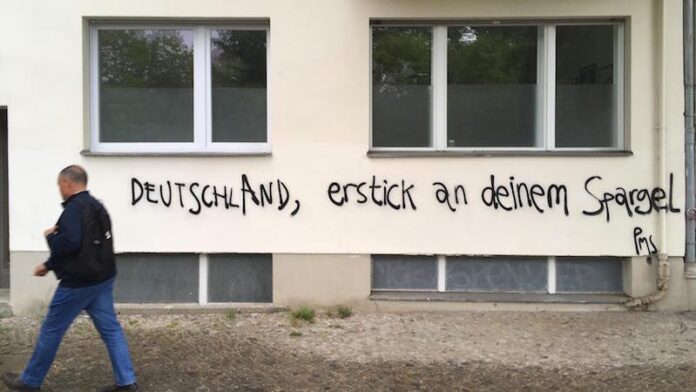

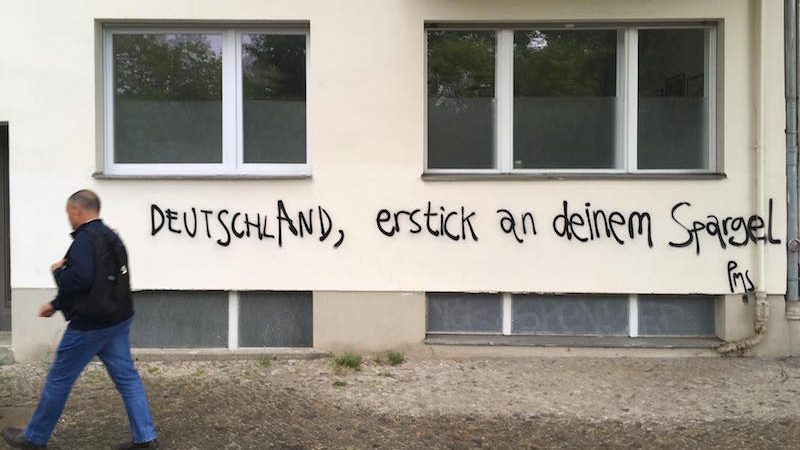

“Germany, choke on your asparagus” reads this graffiti in Wedding, Berlin. Photo (c): Maxim Edwards, May 2020.

In late June, more than 1,500 workers at a meat processing plant in western Germany contracted COVID-19. Once the limit of 50 new infections per 100,000 inhabitants had been surpassed, the lockdown of the facility and its neighbouring village was later extended to the entire district of Gütersloh, in the state of North-Rhine-Westphalia. It was the first lockdown on this scale since Germany relaxed federal restrictions on May 10.

Most of those infected at the Tönnies company’s slaughterhouse were migrant workers from Bulgaria, Poland, and Romania. They are just a handful of the thousands of people from the EU’s eastern member states who head to Germany every year to work in the country’s food industry.

Germany’s epidemiologists have warned that these massive facilities, with their poor ventilation, running fluids, packed assembly lines, and oft-touched metal surfaces, constitute Petri dishes for infection. They have already noted a significant number of COVID-19 infections among slaughterhouse workers, who are now being tested en masse in at least five federal states. But some figures, including North-Rhine-Westphalia’s Prime Minister Armin Laschet, seemingly shifted the blame onto the workers themselves (Laschet has since “clarified” his statements, made in June, after criticism from federal politicians.)

Tönnies now adorns the frontpages of Germany’s leading newspapers; in some publications and on social media, it has become a popular quip to state that the pigs have a bigger lobby in Germany than the precarious workers who slaughter them. That may change. On May 20, Germany’s Minister of Labour Hubertus Heil presented a new law to ban the outsourcing of labour and hiring processes to subcontractors, obliging Germany’s meat companies to commit to minimum labour standards for migrant workers.

With this outbreak, another chapter has unfolded in Germany’s public discussion about the status of seasonal labour migrants. Labour activists from Europe, East and West, are warning that the COVID-19 pandemic has not only illuminated these existing inequalities — it has deepened them.

Choke on your asparagus

In Germany, the coming of spring is traditionally symbolised by the asparagus and strawberries. More recent tradition holds that they are picked by precarious Bulgarian and Romanian migrant workers — Germany’s agricultural sector hired 300,000 migrant workers in 2019 alone. So when the federal government closed the country’s borders in March due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the German agricultural lobby feared that tonnes of produce could be left to rot in the fields. Therefore, on April 2, Berlin agreed to open Germany’s borders to 80,000 seasonal labour migrants over the following two months. The EU instituted a union-wide exception to travel bans for seasonal labourers.

Almost immediately, thousands of Romanians heeded the call. On April 9, images hit social media of 1,800 people crammed into the small international airport in Cluj-Napoca, due to board four flights to Germany. According to some German media reports, several workers had arrived from the Suceava region, which was technically supposed to be under lockdown. What explained the crowds of people at Cluj airport that day?

Both at home and in Germany, these seasonal labourers were accused of recklessness and stupidity for choosing to work abroad during a pandemic. Rights activists and analysts alike criticised this framing as inaccurate, asking not why workers chose to take such risks, but what the German companies benefitting from their labour could do to keep them safe. After all they were, in the words of the EU directive which exempted them from travel bans, “critical workers.”

For many people in rural Bulgaria, Romania, and other eastern European states with poor employment prospects, seasonal labour migration is a matter of survival.

Polina Manolova, a migration researcher at the University of Tübingen, says that the Bulgarian government that the Bulgarian government’s lack of proactive measures to offer social support for workers intensified poverty, or the fear of impoverishment, during the pandemic:

These are people who have been laid off recently, people who aren’t entitled to any unemployment benefit because there are so many conditions they have to fulfil. A lot of people fall out of the social security net, or work in the grey sector, or are self-employed. I follow recruitment agencies on Facebook, and I have never before seen such massive interest in leaving to work on these jobs.

As this anonymous woman explained to Bulgarian National Radio in April:

Финансова е причината да искам да замина. С 20 паудна си пазарувам храна за цялата седмица и от нищо не се лишавам, а тук не мога да си позволя да си купя сьомга всяка седмица. На 30-и април летя, имам организиран чартърен полет от фермата. Пътувам за Англия. Тази година ми е девети сезон, ходя в една и съща ферма. Фермата е за ягоди, малини, къпини, боровинки. Не се притеснявам, там сме затворено общество. От познати, които са там, знам, че има карантинен период. Спим в каравани, по шест човека сме, имаме отделно баня, тоалетна

The reason is financial for me. With 20 pounds I can do my weekly shopping and I don’t deprive myself of anything. Here I can’t even afford to buy fish each week. I am going on a charter flight organised by the company on April 30. This is my ninth season in this farm. It’s a strawberry, raspberry, blackberry, and blueberry farm. I am not worried because we are like a closed society there. My friends there told me that there is a quarantine period. We are six people in a caravan, we have a shared bathroom and a toilet.

Her words also suggest, as several analysts explained to Global Voices, that wage differentials are a necessary but not sufficient way to explain seasonal labour migration. It offers young families a chance to save for their children’s higher education or houses of their own. It offers social capital; for young men in rural areas, it may as well be considered a rite of passage.

This mainstay of rural life in Romania and Bulgaria was not going to be cut short by the pandemic. Facebook groups recruiting farm workers in the UK, Germany, and the Netherlands teemed with eager workers soliciting advice on how to head overseas. A handful of comments on the Bulgarian-language Brigada UK express concern about the coronavirus and social distancing measures, but most seem undeterred, even comments in April when the pandemic was far worse in many countries.

“With the amount of chemicals they spray over there, there’s no way you’ll get COVID-19!” joked one man on the same page.

Life on the fields

When seasonal workers arrived in Germany, caveats applied. EU regulations, as well as instructions drafted by the German Ministry of Agriculture, obliged them to take a generalised health test before entering the country, whereupon they would have to self-isolate for two weeks. Only chartered flights were permitted, rather than the long bus journeys taken by most labour migrants.

Yet much remained the same. Seasonal labourers were still hired by subcontractors and middlemen rather than the farms or slaughterhouses where they worked. Formally paid the German hourly minimum wage of 9.35 euros, they complain that much of that sum is in fact deducted — not always transparently — to cover flights, food, and accommodation which they consider substandard. Dominique John, project coordinator of Faire Mobilität, an NGO which enforces fair working conditions for migrant labourers in Germany, told Global Voices that his colleagues had noted a rise in complaints of this nature in recent months.

Fundamentally, this precarious employment relationship did not change during the pandemic. As one German farmer told the national tabloid Bild in April:

Deutsche kann ich nicht gebrauchen. Stundenlang gebückt auf dem Feld zu arbeiten, sind die meisten Deutschen nicht gewohnt. Sie klagen schnell über Rückenschmerzen… Der Spargel muss alle ein bis anderthalb Tage gestochen werden. Deutsche fordern die Woche ein, zwei Tage frei. Das geht in der Hochsaison nicht. Rumänen ackern auch sonn- und feiertags

I can’t use Germans. Most Germans aren’t used to toiling away in the fields for hours on end. They quickly complain about backaches. But asparagus has to be picked every one to one and a half days. Germans demand one or two days off per week. That doesn’t cut it in the harvest season. Romanians work away on Sunday and public holidays too.

According to an April 2 concept paper drafted by Germany’s Ministry of Agriculture seen by Global Voices, seasonal labour migrants had to be provided with personal protective equipment (PPE) and be able to work and live at a safe distance distanced from one another. However, in light of the usual standards of accommodation for such workers, researchers and activists such as Manolova doubt that even stricter sanitary measures could be enforced across the board.

The following examples, according to labour rights activists, are not unrepresentative of the living conditions of seasonal labour migrants on farms in Germany and neighbouring Austria:

ErntearbeiterInnen sind meist unsichtbar, bestenfalls sieht mensch kleine Gruppen von ihnen am Feld arbeiten. Gestern…

Geplaatst door Sezonieri – Kampagne für die Rechte von Erntehelfer_innen in Österreich op Vrijdag 12 juni 2020

Ieri am fost împreună cu Oskar Brabanski, Sevghin Mayr, IG BAU și WirtschaftsWoche în vizită la muncitorii din…

Geplaatst door Marius Hanganu op Vrijdag 10 juli 2020

In April, other labour activists voice concern at the potential health consequences of the rigorous work regime on the fields:

horror stories from Romanian seasonal workers in Germany continue:

1. Days of quarantine: one. Then, on the fields.

2. Pressured to work 14 hours a day, 100 hours a week!

3. If refusing to work in cold rain, fired on spot. https://t.co/CCdI9e3AWg— Daniela Gabor (@DanielaGabor) April 20, 2020

On April 11, a Romanian man working as an asparagus picker in the southern state of Baden-Württemberg was found dead, and had tested positive for coronavirus. He is believed to have entered the country earlier, on March 20. The same month, Romanian workers from Suceava working at the same farm wrote the following letter to Monitorul de Suceava, a local newspaper, complaining about working conditions during the pandemic. The subcontractor who had dispatched them there, they continued, was no longer responding to their phone calls.

Vă scriu pentru că suntem într-o mare dilemă, suntem în locul în care a murit acel bărbat din Suceava, aici nu sunt condiții de protecție, sunt oameni în izolare care muncesc singuri pe câmp. Astăzi a izolat o echipă întreagă de oameni, aici este o femeie care se simte rău și așteaptă medicul de azi dimineață și nu vine nimeni să o vadă. Se lucrează și în hală la sortat sparanghel, aici oamenii stau unul lângă altul, avem măști pe care le purtăm de 5 zile. Au închis porțile firmei și au pus bodyguard, au mers apoi la oameni în câmp și le-au spus că dacă vine poliția să le spună că e totul bine. Vrem să mergem acasă, nu vrem să murim aici pe capete.

I write to you because we are in a great dilemma. We are in the place where that man from Suceava died. There are no means of protection; there are self-isolating people who work alone in the fields. Today a whole team of people were isolated; there’s a woman who feels ill, she’s been waiting for the doctor to come since the morning and nobody comes to see her. People sort asparagus in the hall and stand next to each other. We have masks that we’ve been wearing for five days. They closed the gates of the compound and put guards there, then went to people in the fields and told them that if the police come, they have to tell them that everything is fine. We want to go home. We do not want to die here.

There are grounds to believe that the distribution of working hours has improved in subsequent months. But in light of the employment relationship, a key question remains: what should happen if an agricultural worker in Germany falls ill from COVID-19?

Last year, the Federal Employment Agency stated that nearly 70 percent of agricultural seasonal labourers in Germany were marginally employed on short term “mini jobs,” and therefore did not qualify for health insurance and German social security guarantees. Furthermore, the maximum period in which foreign workers were allowed to work in Germany without them or their employers contributing to the social security system was raised from 70 to 115 days during the pandemic, potentially prolonging their precarious situation.

Throughout May and June, public interest in the fate of seasonal labour migrants rose, as did fears that the incoming labourers would bring COVID-19 with them.

But what went less widely remarked was that eastern Europe had been comparatively successful in its fight against the pandemic. Despite widespread tropes about migrants “bringing disease” to Europe, it was the Romanian and Bulgarian asparagus pickers, not the consumers, were at greater risk from working in Germany — where the number of COVID-19 infections was far higher than in their homelands.

When the crops have been saved and their saviours return to their home countries, it could be worth revisiting this social media user’s words:

Auch muss ich gerade an diese abstrusen Bilder von voriger Woche denken, wo tausende Erntehelfer eng gedrängt an rumänischen Flughäfen standen.

Und ich frage mich: Wie wahrscheinlich ist es, dass ein rumänischer Erntehelfer hier zum Arzt geht wenn er Husten hat? Wer hilft denen?— Dr. Wu (@Dok_Wu) April 15, 2020

I have to reflect on these abstruse images from the past weeks, where thousands of migrant workers stand back to back in Romanian airports. And I ask myself: how likely is it that a Romanian migrant labourer will go to the doctor here if he has a cough? Who will help him then?

It is a good question. If, indeed, one of those workers is able to visit a doctor in Germany, nothing will be lost in translation — for Germany’s healthcare system, much like many others in Europe, runs with the help of thousands of Romanian doctors who have come in search of a dignified salary. Meanwhile, Romania fights COVID-19 with a shortage of medical personnel.

The new precariat

These examples are German, but they illustrate a story which all Europe shares.

In my own home country of Britain, the question of precarious eastern European labour has become ensnared in a Brexit culture war. Fearing for the fruit harvest, the government launched a “Pick for Britain” campaign in May, extolling patriotic spirit as the solution in a time of closed borders. Few Brits obliged. And so, exceptions to border closures were quickly made for seasonal migrant workers, much to the chagrin of some Brexit supporters. For pro-Europeans, the refusal of their opponents to work on the fields was the strongest evidence of their hypocrisy; precarious labour migrants betokened an idealised European cosmopolitanism drifting out of reach. Between the lines, say experts, a more holistic conversation about labour rights for seasonal migrants was lost.

Valer Simion Cosma, an anthropologist working with labour migrants in rural Romania and an employee of the Zalău History and Art Museum, hopes that the pandemic might raise awareness to Europe’s segmented labour economy:

The management of fresh food supply chains in Europe’s transnational agribusiness relies on cheap, non-unionised, and privately managed labour from low-wage Eastern European countries. The costs and benefits of this material structure are under-appreciated. West European farming benefits from massive EU and national subsidies, crowding out agricultural exports from the Global South. Yet pay and work conditions in the parts of European food supply chains that are not yet automated (such as fresh produce or meatpacking) remain precarious. International supermarkets pit producers against each other, who in turn rely on wage suppression to defend the sectors’ relatively small margins. While in theory, the East European workers enjoy the legal protections awarded to formal labour by EU law, the COVID-19 pandemic has exposed, and in some cases sharpened, their often exploitative work conditions. This occurred not just in countries with large informal sectors, weak labour unions a dual labor markets such as Greece, Spain or Italy, but also in countries like Germany, where economic informality is low and, for all the recent erosion, labour relations.

For Hein de Haas, Professor of Sociology at the University of Amsterdam and director of the Migration Institute, the role of seasonal labour migrants in a time of otherwise closed borders underscores the fact that complete autarky has become a fantasy:

There’s a chronic demand for labour across Europe, and this shows it. You can have Brexit or no Brexit, you’re still going to need those workers, and there are few remaining places in Europe other than Romania where you can get them. Over the past 30 years, we’ve been through a process of liberalisation of economies, there have been much more short-term labour contracts and flexibility to recruit migrant labourers, and that’s in total opposition to the publicly stated desire to have less immigration; you can’t have both. You cannot on the one hand liberalise the economy and give more leeway to labour movement and then say that you want less immigration. Politicians play this game about closing borders because there’s political benefits, but at the same time it’s clear.

Trade unions also have to accept that local workers aren’t available for those jobs. It’s also not true that if the wages and conditions were improved, local workers would do that work — look at its social status. Perhaps students will do it, but once they graduate they’re not going to do this. Politicians can say that they want unemployed people to do that work, but the problem is that picking strawberries, asparagus isn’t an easy job! It requires getting up very early and being very motivated, and actually requires some skills. You won’t often find that among other workers. It has proven a complete illusion that you can do without this. We’re talking about very specific sectors — agriculture is one, care work is another, restaurants and dishwashing, hotel industry is another. These sectors can only exist because of that labour coming in.

For the Romanian philosopher Vasile Ernu, the pandemic prompts uncomfortable realisations about the place of his country in the global economy, and the frustrated hopes of the transition to market capitalism. Eastern Europe, he concluded in a column in April for Libertatea, provides the continent’s precariat:

Însă resursa umană cu care România a mai rămas nu mai este una super calificată, adică bine plătită, ci o resursă umană necalificată numită „forţă de muncă ieftină”. Aş spune chiar foarte ieftină şi prost plătită. Atât de ieftină, încît se vinde „sezonier”, „en-gros”, aproape ca buştenii. Dar dacă buştenii se reîntorc în ţară sub forma unor mărfuri prelucrate în fabrici şi cu un preţ mai mare, cetăţenii, „forţa de muncă ieftină”, revin în ţară mai obosiţi, mai bolnavi, mai bătrâni, chiar dacă cu ceva bani adunaţi. Citeşte întreaga ştire: Noul proiect de ţară este neoiobăgia. Statul nu face diferența între bușteni și oameni… […] Avem stare de urgenţă, sau dispare la un telefon din Germania? […] Ce garanţii au aceşti oameni, ce asigurări, ce condiţii sanitare etc.? Ei pleacă pentru câteva luni, căci sunt “sezonieri”: cine le plăteşte carantina când se întorc? Statul german, angajatorii sau statul român? […] Care este proiectul nostru de ţară?

The human resource Romania is left with is no longer highly qualified, or rather, well-paid, but an unqualified resource known as “cheap labour.” Cheap, or poorly paid. So cheap that it is sold “seasonally,” and “wholesale” — almost like logs. But if the logs return to their country of origin in the form of goods processed in factories, to be sold at a higher price, the “cheap labour” citizens return to their country more tired, sick, and older, even if they have raised a little money. Our country’s new project is neo-feudalism. The state does not differentiate between logs and human beings. […] So, do we have a state of emergency, or does it disappear with a phone call from Germany? […] What guarantees do these people have? What insurance, what healthcare? They leave after a few months, because they are “seasonal.” Who pays for their quarantine when they return: the German state, the Romanian state, or their employers? […] What is our national project?

As borders were closed across Europe, some of the continent’s most vulnerable workers saw themselves labelled “critical” and “essential” by Brussels and Berlin. It was a flattering acknowledgement, but one which implicitly invited comparison with their less than flattering employment rights and precarious existence.

If the post-pandemic world returns to “normal,” it behoves Europeans to ask once more about the how our normality came to be and at a cost to whom — the cost to those who toil unseen, the better to nourish our illusions that it may continue forever.

Welcome to www.network.wales

We’re your new go-to platform for connecting communities across Wales—through local news, petitions, events, and meaningful conversations.

Have something to share?

Whether you're passionate about writing, have a story to tell, or just want your voice heard, we’d love to hear from you! Contact Us Here or email: [email protected]